Before Columbine, there were two headline-making massacres at U.S. schools.

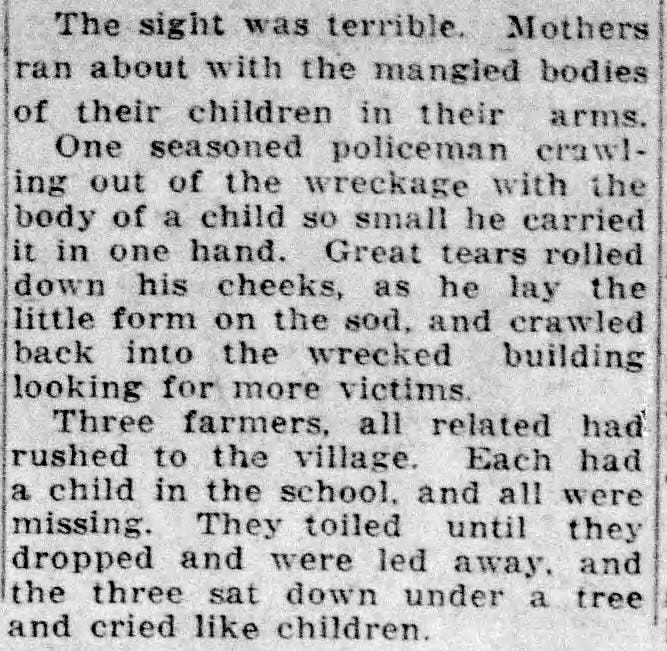

This is from the Flint Journal reporting on the country’s worst mass murder at a schoolhouse, the bombing of the Bath Consolidated School (grades one through 12) in Michigan on May 18, 1927, a long time ago.

A financially failing farmer and school board treasurer, Andrew Kehoe, a man pissed off about school taxes and a lost township clerk election, blew to bits 37 students, most from the lower grades, two teachers, and six adults, including himself. Somehow he’d hid 900 pounds of dynamite in the school, though most of it didn’t go off.

The wreckage of the Bath Consolidated School — the deadliest act of mass murder in a U.S. school

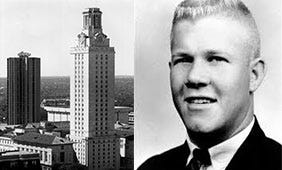

Nearly four decades later, on Aug. 1, 1966, Marine veteran Charles Whitman -- wracked by a brain tumor — packed a footlocker with firearms and took it to the observation deck of the 307-foot clock tower at the University of Texas at Austin. He killed three people inside the tower, 12 below, including an unborn child and injured 31 other pedestrians before cops took him out.

The tower and the sniper

Until Columbine, these massacres were uncommon and many years apart but then came April 20, 1999 -- Hitler's birthday -- when a nightmare at the school in Littleton, Col., changed all that.

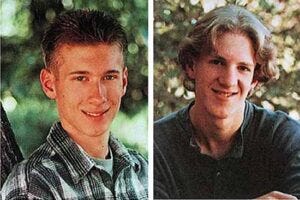

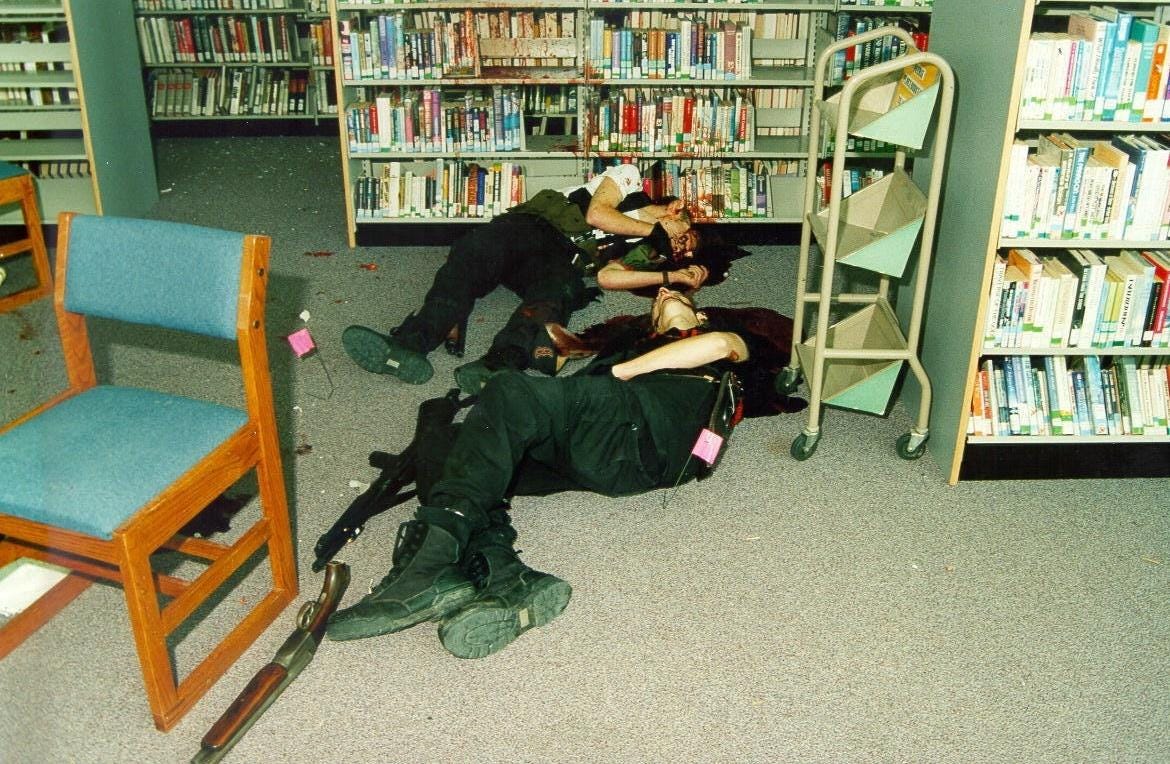

Two seniors Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris shot dead a teacher and 12 students and injured 23 more, before killing themselves in the school library.

Eric Harris (l) and Dylan Klebold

The massacre was a pivotal event. From that moment on, similar tragedies seem to come one after the other as "Columbine" became a byword for the American bad dream. Schools became a target and fear was now part of the student curriculum.

Since 1999, depending on criteria used by various fact-checkers, there have been at least 400 school shootings, which claimed at least 203 lives and left more than 400 injured.

Watching terrified youngsters fleeing schools is too often "breaking news." Lots of thoughts and prayers from pathetic politicians but no rational solutions.

I got to know one Columbine kid. Nathan Dykeman. He'll never talk to me again and deserves my apology. I'll explain.

He was a senior and fellow classmate of Klebold and Harris, and arguably their best friend.

In the media frenzy surrounding the tragedy, we, at the National ENQUIRER signed him up for an exclusive interview. He was to be paid $10,000.

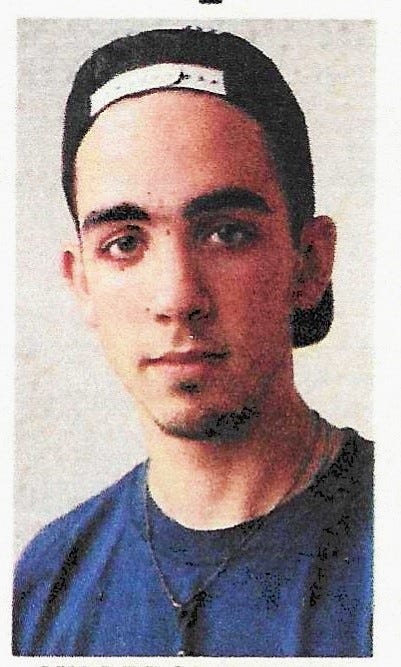

Nathan Dykeman

After a grilling from numerous law enforcement agencies, Nate had headed East from the Colorado home he shared with his mom and stepfather.

He moved to Florida, near Tampa, to take up residence with his biological dad, stepmom and stepsister. That was always the plan since Nate wanted to get his higher education in the Sunshine state.

I had the assignment to interview him and drove over from our Palm Beach County headquarters to talk to the student.

Nate was nervous. These were his best buddies who had just made frightening history. He had a wealth of information that was shocking and still unreported at the time. He was a close enough friend of the shooters that he knew they'd died virgins when they blew their brains out in the school library.

He recalled silly high school stuff. It seems Dylan Klebold hated the singer Richard Marx and Nate would tease his pal by calling him up and playing his hit song "Right Here Waiting for You."

"He would scream," said Nate.

But aside from the goofy pranks, Nate had begun to realize that he saw things that probably would have set off alarms had they happened today when school shootings are all too common.

Klebold’s parents had asked him if he could explain why it happened. “I couldn’t,” he told me. “I’d give anything if I could go back in time and talk some sense into my friends.”

Nate knew that a year before the massacre, in March of 1998, Klebold and Harris were arrested for breaking into a van and stealing electronic equipment. As their families dealt with the crime, Nate said Harris' parents found a pipe bomb in their son's room in a shoe box.

"Eric later told me his dad took him somewhere safe and made him detonate it. His parents never told the cops," said Nate. They feared it would not help in the matter of the van theft, for which the two friends were eventually sentenced to a juvenile diversion program.

Harris later showed Nate two other pipe bombs he had manufactured. "Eric was sitting on his bed tossing them up in the air and catching them," Dykeman told me.

In the months before the assault on the school, Nate learned that his friends were into guns in a big way.

During a video production class, Nate wandered over behind Eric and Dylan.

"They were watching a video on the computer. It was the two of them shooting in the woods," said Nate.

Authorities would learn that the pair were firing the same weapons used in the massacre -- a TEC 9 machine pistol, a pump-action shotgun, an assault rifle and a sawed -off shotgun.

Nate had never seen Klebold with a gun and he'd only seen Harris use a BB gun to shoot crickets.

In a video that Nate made while driving to school with Klebold three months before the killings, Dylan shouts, "Load the torpedoes!" as Columbine comes into view.

He and Harris had already been planning their assault, according to journals they kept.

The school's senior prom was three days before the massacre. Nate and Dylan went with their dates but Harris, not having a date, skipped it. He joined his friends, however, at an early morning after-prom party held in a nearby park.

Nate said Harris and Klebold disappeared for a couple of hours. Later, he wondered if the two went to the school to plant some of the bombs they intended to use.

Their store of weapons included 95 explosive devices -- enough firepower to kill hundreds of students.

There were 48 carbon dioxide bombs, 27 pipe bombs, 11 half-gallon propane containers, seven incendiary devices with 40-plus gallons of flammable liquid and two duffel bag bombs with 20-pound liquefied-petroleum gas tanks.

Fortunately most failed to explode due to electronic problems and the use of unstable fireworks powder.

Nate told me he wondered if his friend Klebold "naively figured he'd live through this."

A strange story Klebold wrote for creative writing class "was about a guy in a city that kills people and never gets caught," said Nate.

On the day of the massacre, Nate had a bad feeling.

His friends had skipped an early morning bowling class. When both were absent from the language arts class he shared with them, he found that odd. While they would cut class, they didn't typically cut so many at the same time.

Nate lived close to the school and when he left campus for lunch at home around 11:20 a.m., he spotted Harris walking from the junior parking lot carrying a bag. He thought it strange that Harris was using the junior lot instead of the senior lot.

When Nate tried to return to school, he found it blocked off by police barricades. He raced home.

Through binoculars, Nate and his stepfather Victor Goode watch the event unfolding at the school. The student told his stepdad that he had this feeling Harris and Klebold might be involved.

Nate was especially close to the Klebold family. He called their home and Dylan's father, Tom, picked up, still unaware of what was happening at the school.

It was Nate who told Dylan's dad he feared his son was involved.

He informed Tom Klebold that Dylan didn’t show up for classes and there's a shooting. He told Dylan's father to check his son’s closet for the boy’s trench coat, the school choice of dress for Dylan and Eric Harris.

If it wasn’t there, it would mean he was at the school. It wasn’t. Tom Klebold hung up, and called 911 to warn them of Dylan’s possible involvement -- then he called a lawyer.

Crime scene photo of Harris and Klebold

My story began with Nate's revelations about the killers. It didn't need to be exaggerated.

But an editor who shall remain nameless, got his hands on the copy and changed the theme of the piece.

Over my objections, the story was reworked to focus on two messages Klebold and Harris wrote in Nathan Dykeman's 1998 yearbook from their junior year.

The headline read "Secret Plot To Kill H'wood Stars."

"Kill jiggy...kill puffy...kill hanson...kill Richard Marx!!" wrote Klebold. He didn't like the music of Will Smith, P. Diddy, the teen trio Hansen and Marx.

There was one comment that said, "Die Connie" who was a manager at a supermarket where Klebold had bagged groceries for a while.

But to label this a secret plot was ridiculous.

In his yearbook message, Eric Harris, who was taking German, wrote the phrase "Ich bin Gott" (I am God) and urged Dykeman to "follow your fucking animal instincts. . .if it moves kill it, if it doesn't burn it. . ." It's signed REB, a nickname Harris gave himself.

Of course, these yearbook ramblings are worth mentioning but not as the major thrust of Dykeman's information.

When the story ran, Nate told other media outlets that we misrepresented him and I don't blame him. My apologies. Some editors suck.

He took heat in the press for selling us his tale but also for taking $16,000 from ABC for purchase of the video he made while riding to school with Klebold. He also gave them an interview.

“I was broke. I had to leave my truck in Oklahoma where it broke down,” he said. “Now my college tuition is paid for. I’ve been criticized enough for this. What was it I did wrong? I know at least a dozen people who were offered money from the media.”

It was probably more than a dozen.

On the second day of interviewing him, though, he showed off his new ride. It wasn't a truck. It was a red Mustang. Used, but a nice car. I asked him if he'd mind if I keyed it. He didn't laugh.

Then I took him and his family out for a dinner on the ENQUIRER at the world-famous Bern's Steak House near Tampa. Always wanted to eat there.

I heard that Dykeman's married with kids and happy. I'm glad.

The Colorado nightmare still makes the news.

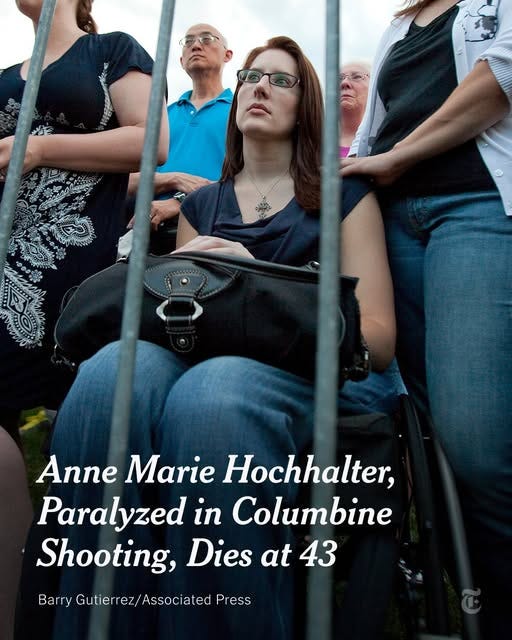

On February 16, this year, Anne Marie Hochhalter died of sepsis. A Columbine junior when Harris shot her as she ate lunch outside the cafeteria, she was paralyzed from the waist down.

She lived with intense pain. Her mother committed suicide six months after the tragedy. Anne Marie wondered if she could have helped her more.

A coroner ruled her death a homicide -- the 14th Columbine fatality.

A sad tale, Don. I think we all feel bad about stories that were misrepresented by a nameless editor in search of a headline that would sell more papers. In fact, I can probably name the editor. His pushing stories into the realm of fiction was one of the reasons I quit a year after your Columbine story ran.

These stories are fabulous! Each one entirely different from the rest. Economy of prose. And they keep getting better. I am a big fan of his work. Hats off, Mr. Gentile ! Keep ‘em coming.