“Fast Eddie” Kirkman

It was not your typical marathon.

This race was a New York City tradition around St. Patrick's Day when participants raced from one Irish bar for about two miles along a boulevard in Queens to another Irish bar.

The prize was a round-trip anytime plane ticket to the Emerald Isle. However, the race had a saloon gimmick.

Runners ran holding a circular waiter's tray in one hand atop of which sat a mugful of brew. To win, you had to come in first with the least amount of spillage.

But there was a loophole in the rules that caught the attention of Edward Kirkman, a veteran New York Daily News reporter of some note. We knew him at the paper as "Fast Eddie," because he was a hustler, akin to the character Paul Newman played in the movie.

And "Fast Eddie" came up with a scheme to enter a young reporter in the race who'd do a first-person story and show him, hands down, how to win that trip to Ireland. The scheme, of course, wouldn't be in the final write.

I'll get to that but let me introduce Mr. Kirkman.

On April 25, 2000, two years before he died he sat down and wrote his own obituary.

Who does that? But, Eddie noted, "I'm no single paragraph guy."

He wasn't. He had 35 journalism awards. When I started as a copyboy at the Daily News in 1967, Kirkman was already a legend as a cop reporter and had been running the paper's police bureau for years.

"Fast Eddie" lived in the world of Anastasia, Colombo, Profaci, Bonanno and Gambino -- and mob rat Joe Valachi.

He was on the streets covering the so-called "Mad Bomber" who frightened New Yorkers like Son of Sam would do.

He wrote about the beat cops, the good ones and at times, the bad ones.

Some of “Fast Eddie’s” bylines. From mobsters, to a cop saving a dog, to a pair of struggling actors getting free publicity because they were taken hostage in a bank.

When Eddie came on board at the News in the late 1940s, it was a different time in journalism. For instance, gun permits were readily made available to press guys who wanted them.

Eddie, a flashy dresser, had to tell his tailor, one who also serviced cops, that, no, he didn't carry a gun and didn't need the side pocket stitched into his suits to accommodate a firearm.

He was a charmer with a quick wit, who'd make you laugh even when he insulted you.

One of his colleagues was writer Don Flynn, who wrote plays in his spare time, but wound up with many rejection letters.

"He would always goof on Flynn," said Larry Celona, a New York Post reporter who started his career at the Daily News.

"He'd put two fingers close together and say, 'Tennessee' -- that's what he called him --'you almost got it. It's a 'A Train Named Desire,' or a 'Dog on a Hot Tin Roof.' or it's 'The Night of the Lizard.' Flynn would laugh."

Somewhere out on the Manhattan streets at some scene of mayhem, "Fast Eddie" met and bonded with photographer Diane Arbus, who would go on to shutterbug immortality, her life ending in suicide.

He owned an Arbus print that was part of a Museum of Modern Art retrospective. A notation next to the photo noted his close friendship with the unique shutterbug.

One of “Fast Eddie’s” good friends

Many Daily News reporters agreed that no one could work the phone on a news story like "Fast Eddie." He was sometimes working two of them at a time.

"I watched Kirkman work the phone on a cop story and it was like a masterpiece the way he did it," said former News writer Neal Hirschfeld, author, screenwriter and prize-winning journalist.

"He was working a murder so he calls up the scene, the phone at the home where it happened."

A detective investigating the crime picked up.

Eddie didn't blink, said Hirschfeld, and told the detective something like, "This is Sgt. O'Halloran down in operations. What we got down there?"

By the end of the call, Kirkman had all the crime details.

Hirschfeld asked him, "What if the guy who picked up was a lieutenant? He said then he'd have been Captain so-and-so."

Mike Pearl, a renowned New York Post crime reporter who just turned 95 (God bless him), worked the streets with Kirkman and called "Fast Eddie" the "best reporter I ever worked with."

And that's saying something. Pearl worked his way through four newspapers that folded in the Big Apple back in the day.

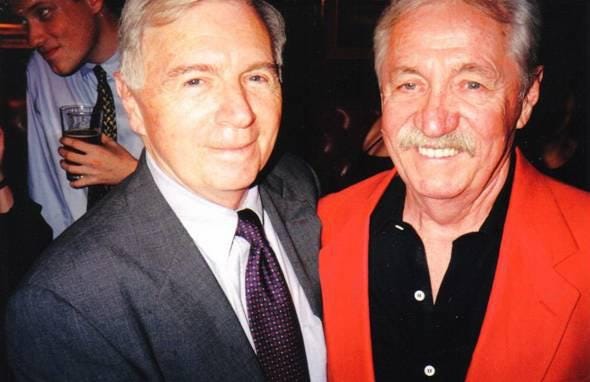

New York Post scribe Mike Pearl (l) and his friendly rival “Fast Eddie” Kirkman

He recalled a story about Kirkman and the hunt for New York's Mad Bomber in the 40s and 50s.

For 14 years, George Metesky, a nut with a beef against Con Edison, terrorized NYC, planting 33 pipe bomb-like devices (22 went off) all over Manhattan.

Bombs were left in the subway system, phone booths, storage lockers and restrooms in public buildings, including Grand Central Station, Penn Station, Radio City Music Hall, the New York Public Library, and the Port Authority Bus Terminal.

No one actually died in the explosions although there were some injuries during the long crime spree and the New York press was always hungry for any little tidbit about the elusive maniac before he was caught.

"In December of 1956," said Pearl, "several reporters, myself included, cornered the closed-mouth Chief of Detectives James Leggett seeking new information on the Mad Bomber.

"After ducking all of our questions, Leggett finally said: "'The Mad Bomber could be anybody.'"

"'Then I might be The Mad Bomber?'" asked Eddie Kirkman

"'It could be you.' Leggett said. 'It could be me -- No! It can't be me. I'm left handed.'"

Pearl recalled vaguely that somehow the revelation that the bomber was right-handed was important and "gave us a story. And from that day on the Chief of Detectives was known as Lefty Leggett."

That was Kirkman. There are no stupid questions, something he passed on to many reporters fortunate enough to work for him during his many years as Daily News police bureau chief.

"He was a mentor, slick, a 'Front Page' type, friendly with a lot of police brass. I learned at his knee," said veteran Newser Bob Kapstatter, a chief of the Brooklyn and Bronx bureaus and a city editor

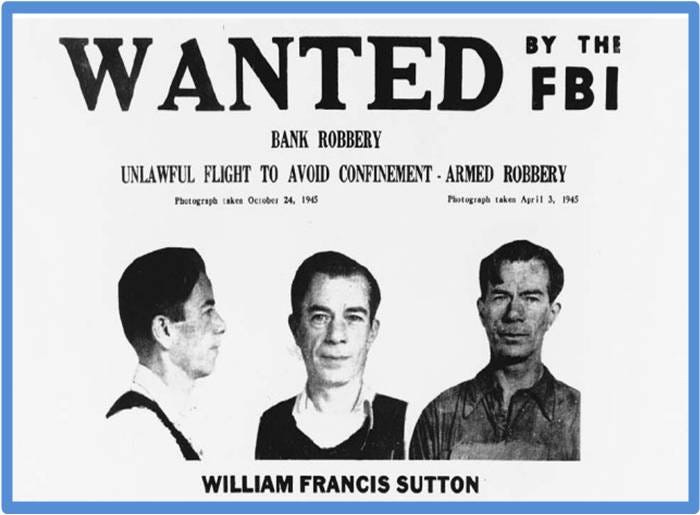

One of Kirkman's contacts was the lawyer for notorious bank robber Willie Sutton who arranged for "Fast Eddie" to interview the famous thief when he was released from Attica State Prison on Christmas Eve, 1969.

At the time, the Daily News had a plane and along with photog Gordon Rynders, Eddie was flown to the upstate New York prison, where he waited until Sutton, suitcase in hand, walked out.

With a smile, Willie flew off with Eddie, who liked to say he "kidnapped" Sutton, and planted him at his home on Long Island to keep him from the competition.

Eddie's kids opened their presents on Christmas Day with Willie Sutton sitting at the breakfast table.

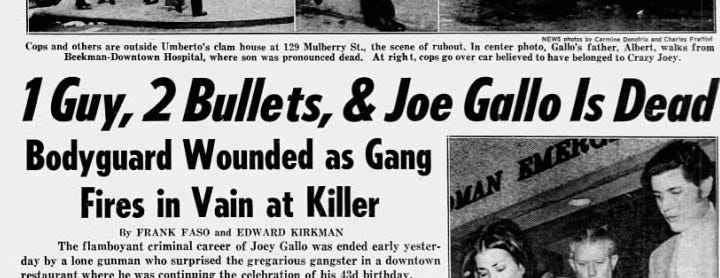

By 1979, the year that mob boss Carmine Galante was gunned down in a hail of bullets in Brooklyn (cigar still in his mouth), Kirkman (who joked the death was an obvious suicide), had an envied resume.

The late Carmine Galante

He'd covered the Patty Hearst trial, the Little Italy rubout of "Crazy Joe" Gallo, the theft of the "Star of India" and other rare gems from the Museum of Natural History, the sinking of the Andrea Doria, and the deadly collision of two passenger planes over New York City.

He went undercover as a bum, spending nights in the Municipal Lodging House for Men, to expose criminal acts on residents in a series dubbed "House of a Hundred Horrors."

Along with his reporter duties, he was also writing a Long Island high school sports column for the News, teaching a journalism course at St. John's University in Queens, and co-authoring a book on how to play the game of baseball with N.Y. Mets star Ed Kranepool.

By 1980, however, "Fast Eddie" was being put out to pasture by a few editors he'd had run-ins with. In my experience, there were editors who liked to do that.

"He was smarter than the city desk editors he worked for and that was his biggest problem," said Pearl.

Kirkman didn't deserve what was happening. He'd called in favors from police brass he knew to help one particular editor who landed in big trouble with the law. And I can tell you, we knew about it at the paper.

When he was transferred out of the spotlight of the main city room in Manhattan to the Queens bureau, "it was the first step on his way to the gulag," recalled former News reporter Tom Hanrahan.

Hanrahan, himself, was working in the bureau when "Fast Eddie" showed up and the two became good friends.

So, when the Irish race caper of 1980 formed in Kirkman's head, Tommy was all in.

"He called me Man-O-War, like the racehorse," said Hanrahan, at the time a 6-foot-3, buff 205-pounder who played football for Princeton.

Kirkman told Tommy about the loophole. Nothing in the rules, he said, presents a runner from putting their free hand over the top of the mug.

Two days before the race, Kirkman and Hanrahan went to the site of the event along Northern Blvd., and practiced the technique.

"My right hand was under the center of the tray and I put my left hand over the top of the mug. Now there was pressure from below and pressure from above. It worked," said Hanrahan.

"Eddie said, 'You don't have to win the foot race. You can finish in the middle. All you have to do is complete the course, spilling the least amount of beer.'"

The next day was a dry run for all 123 runners who'd signed up to win that trip to Ireland. Kirkman wrote the story for the Daily News about Tommy's efforts in that warm-up event.

To keep the hustle a secret, Hanrahan deliberately dropped the tray and mug just minutes after the race began. He picked up the now-empty glass, grabbed the tray and finished the race a total loser.

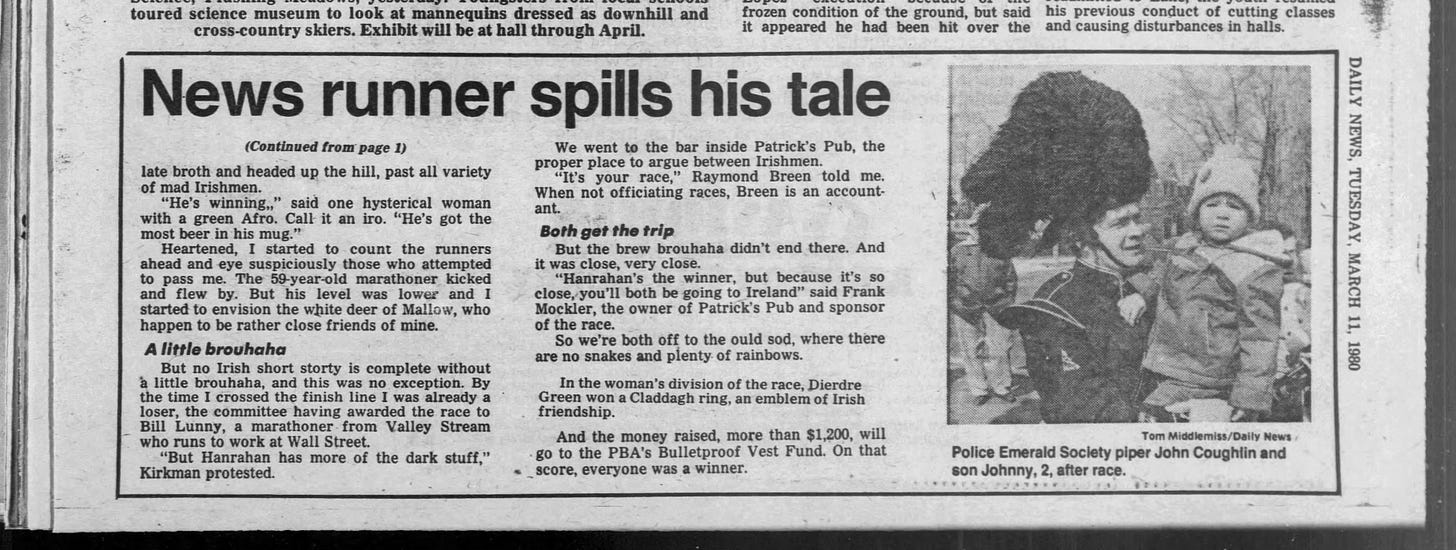

Tommy in the dry run race, before he dropped the tray on purpose.

Now came, Monday, March 10, race day.

The runners, trays and filled mugs in hand, gathered at the starting line in front of the Harp & Mandolin. Down the road was Patrick's Pub, the finish line.

Both establishments, by the way, made the best Irish coffees in town and were owned by Irish tavern-keeper Frank Mockler and his family, sponsors of the race. The $1,230 in entry fees was to be donated to a fund that purchased bullet-proof vests for the NYPD.

The department's Emerald Society Pipers struck up "The Garry Owen" as the joggers took off. (The "brew" in the mugs was actually Hershey syrup mixed with water that passed for Guinness.)

Past Dunkin' Donuts, past the Adrian Motel, Rudi’s Italian Deli, Parrot Jungle and a golf driving range ran Man-of-War, his left hand planted on the top of the mug.

Per Fast Eddie's instructions, he didn't try to be the first runner to the finish line. He jogged steadily, aiming to make sure to keep as much liquid in the mug as possible.

"I finished about 14th," said Tommy. 'No one had seen me put my hand on the mug. And no one else thought to do it."

However, when he entered Patrick's Pub, the judge, an accountant friend of owner Mockler, had already declared the winner to be Bill Lunney, a marathoner from Long Island who came in first across the finish line.

Hold on a minute, said "Fast Eddie," who was waiting for Tommy to arrive.

"Hanrahan has more of the dark stuff," he pointed out.

The accountant, Raymond Breen, took a look and had to admit the obvious. The Daily News reporter had more brew in the glass than Lunney and anyone else who'd finished ahead of him.

"It's your race," said Breen.

And that's when Mrs. Lunney, who was born in Irland and had planned to use the ticket her husband won for a trip to the homeland, got her Irish up.

She directed a steady stream of obscenity at Tommy, accused him of cheating and told him to hand over the plane ticket.

Bar owner Frank Mockler, fearing that it would be thought he'd somehow fixed the race for the Daily News reporter, decided Lunney would also get a ticket to Ireland.

“Man-O-War” Hanrahan’s first-person write — no mention of “Fast Eddie’s” plan.

"That was all Eddie's doing," said Tommy.

(As a side note, I always wondered why there was a different prize for the woman who finished first among the females in the race, a claddagh ring, an Irish symbol of friendship. Not exactly a free trip to Ireland.)

A rumor quickly spread among my fellow reporters at the Daily News that somehow crazy Tommy had cheated. He didn't tell me the real story until a few weeks ago.

"Eddie was definitely sticking it to the News, to embarrass the paper for the way they were treating him," said Hanrahan.

"Fast Eddie" was soon transferred to the minimally staffed Suffolk County bureau, out on the ass-end of Long Island, and took early retirement in 1987.

He taught journalism at the Suffolk County Community College and passed away in 2002 at 75.

Some weeks back, I was talking to friend Larry Celona, who still toils for the New York Post and mentioned I was thinking of writing my own obit so people remember my career.

To my surprise, Celona said, "Eddie Kirkman did it."

Larry Celona was Kirkman's protege. He took "Fast Eddie's" journalism class at St. John's and is in the business at his teacher's urgings.

"The class was at eight. Kirkman came in at nine. He said the only ones up at eight are hookers coming home from work and bank robbers going to work," Celona recalled.

Other writers at the News also taught journalism classes but not like Kirkman.

One of them, Tom Pugh, used to say, he "would have to fuckin' have a syllabus, books, and stuff to prepare," said Celona. "Kirkman just does two hours of Kirkman."

"Fast Eddie" regaled his students with his own experiences and had them write about his many law enforcement pals who appeared as guest speakers.

Celona, who regularly joined Kirkman for dinner in Little Italy, has gone on to be, arguably, the premiere police reporter in NYC. His sources among law enforcement are mind-boggling.

If you Google him, up pop reams of his New York Post cop stories, countless exclusives among them.

He broke the news that Robert Durst, the New York real estate heir and murderer had been nabbed on the run in Galveston. "No one in Texas knew who he was at the time," said Celona, who got a tip from a detective source.

He was the first to report Jeffrey Epstein's suicide in jail.

A page one story revealed John Gotti had offered a million dollars for the "head of Sammy the Bull," who ratted out his Mafia boss.

And Celona beat everyone in the country with the news that John F. Kennedy Jr.'s plane had gone down.

For all intents and purposes, Celona is Kirkman.

When "Fast Eddie" died, Larry fought for the right to acquire the press plates "NYP8" that belonged to his former journalism teacher.

"I did it to honor him," said Celona. "When someone asks why I have such a low number, I tell the story about Eddie Kirkman."

I had Larry send me a copy of the obit Kirkman wrote. He listed his accomplishments and asked his son to send copies to Celona, Owen Moritz of the Daily News and Kathy Kerr, a Long Island Newsday reporter.

One detail that did not make it into the stories of his demise was the section Kirkman labeled "Advice." It read, "Never believe an editor. They were lousy reporters who butt-kissed their way into better-paying jobs."

Tom Kirkman followed his dad's instructions and in a letter to Celona told of "Fast Eddie's" last hustle.

"The day before he died he had in the funeral director, a nice young Irish girl. Among the many details, he broached the subject of 'accommodation' on the costs. When she asked what exactly he had in mind, he quipped, 'I don't know, I never died before.' Not only did she leave laughing and liking him, but he actually hustled her on the price. That was my father. . ."

"Fast Eddie" -- definitely not a single paragraph guy.

A wonderful story about the newsmen who made New York legendary… reporters who told the thrilling Big Apple stories with all the color and verve they deserved. Don, you did a very nice job of telling their stories and memorializing their feats of journalistic wonder. Thanks, Ed S.

Great story, Don. Those were the days when newspapers had real reporters. Keep the stories coming!

BTW, I met my future wife after a 17-Mille beer-bike race. No, I didn’t participate in the race. I just spent the afternoon drinking at the final bar with all the girls waiting there for the race to end.