Let me tell you a tale about Robert Ziobro, who was always on a stairway to heaven.

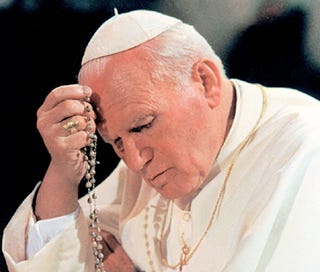

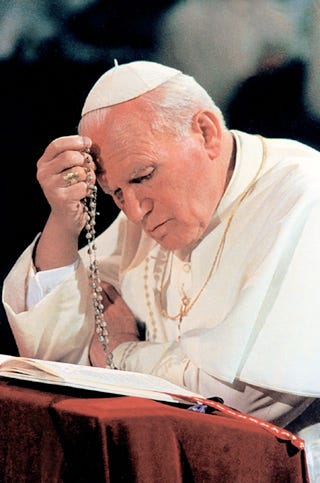

Pope Benedict the XVI honored him with two hotshot Catholic VIP awards. And it's a good possibility that Saint John Paul II, the Polish-born Pontiff, the one that got shot, cured him of cancer with a miracle -- yes, an actual miracle.

But more about that later.

I know Ziobro. As kids, we crossed paths for a while. Some guys called him Zeke. He didn't like it. "They would bust my chops," he'd say.

Officially, his title is Brother Robert Ziobro SC, a member of the Brothers of the Sacred Heart, a Catholic teaching order. For non-Catholics, think of them as male nuns. Members take vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. And, just like nuns, some of them whacked little Catholic boys when we disobeyed.

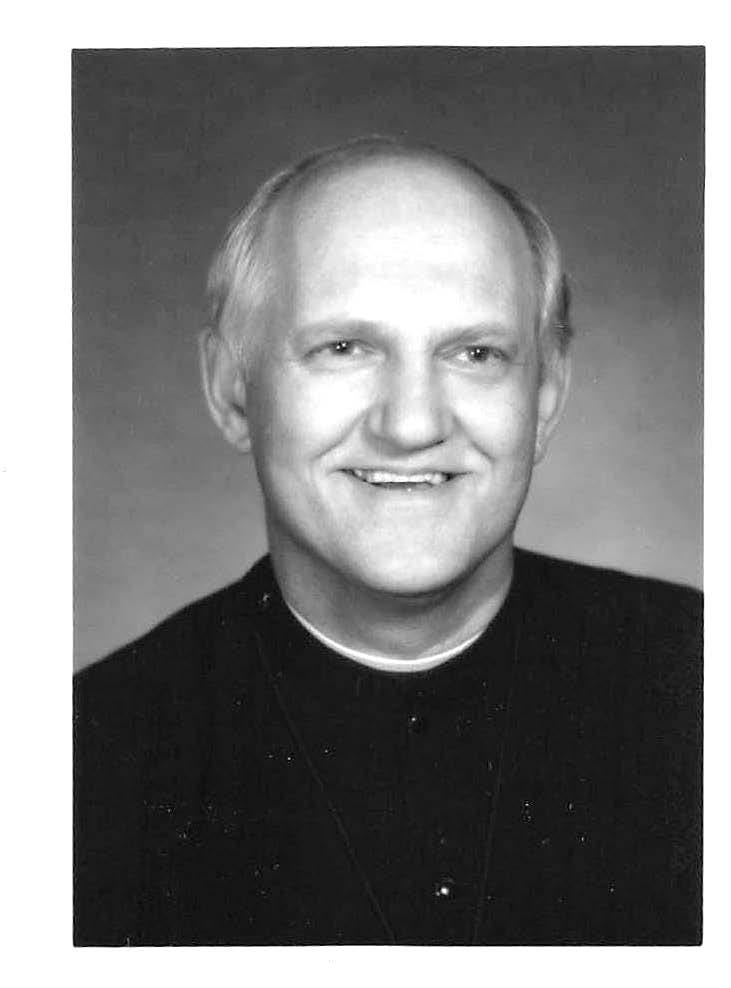

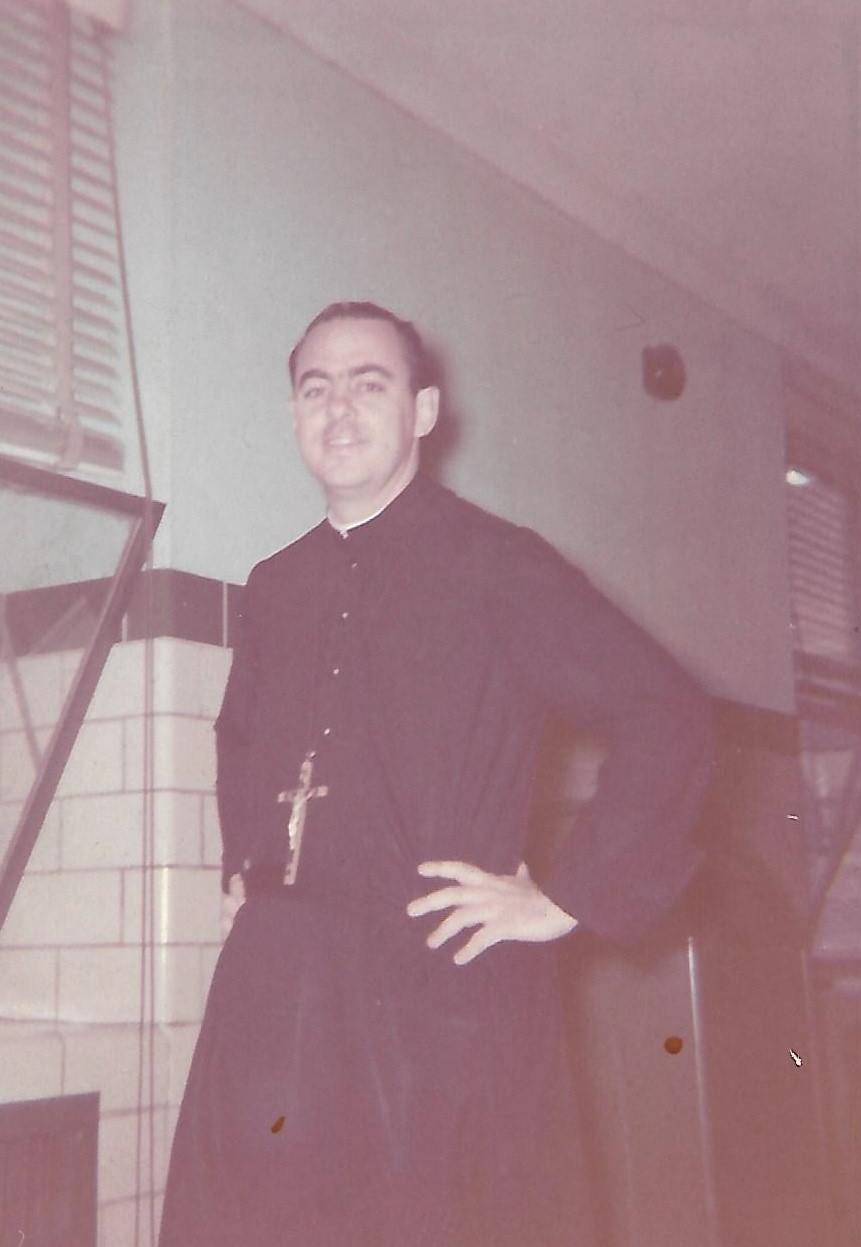

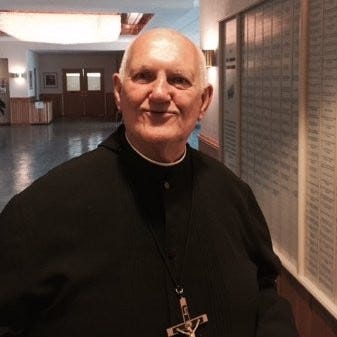

Brother Robert Ziobro

I met Ziobro in 1961. I was 13. He was 15. Both of us were living away from home in the high school/religious complex where those with a "calling" to serve Jesus prepared to become a Brother of the Sacred Heart.

Yes, I wanted to be one, taking that road less travelled as Frost put it. I would have wound up as Brother Donald Gentile, wearing a really cool-looking black cassock, cinctured at the waist and with a crucifix dangling at chest high.

I'd be teaching religion and school subjects to young Catholic students at some learning facility the brothers ran. Maybe Africa. They have a presence there in addition to the U.S., Canada, Europe, the Philippines and South America.

For me, however, final vows were not to be. I realized I didn't want to forego sex the rest of my life, and being poor or obedient didn't appeal to me. Plus, I was really homesick.

But I lasted two years in that spiritual enclave attending freshman and sophomore high school classes, praying, attending daily Mass, and doing chores such as buffing the wax shine on the study room floor using one of those industrial-size machines.

It was a good time in my life.

The image of Jesus with his visible heart is iconic. It means love, the love Jesus has for us and the love we should share with others. Devotion to the Sacred Heart asks that we seek repentance for our sins and the sins of mankind. Jesus things. Good things.

These Sacred Heart brothers taught me at St. Philip Neri elementary school in the Bronx. It was those weird developing years between 10 and 13, grades five through eight, when we'd finally left the nuns behind.

Brothers Albert, Gwynn, Giles, Aidan, Stanley, Boniface and Bruce were important at that young age.

They had a sense of holy mystery about them, since, at the time, they were only using one name. That name was one they'd chosen, not their actual given name.

It was a game among we kids to get them to confess their real names. But it was like "omerta" for them.

They coached our basketball, baseball and football teams. I was on all those teams. And you really got to know these guys. They were your buddies. Our heroes.

I remember watching Brother Giles, using just one arm, nonchalantly toss a basketball the length of the school's court and into the basket.

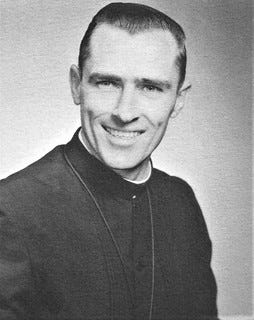

Brother Aidan had movie star good looks and could hit a baseball a mile.

Brother Aidan

Brother Albert, the football coach, went ice skating with students after school and sometimes on weekends.

You got to visit with them at their home, a comfortable house, with a wraparound porch as I remember, located a couple of blocks from the school.

I took an IQ test there from one of the brothers who was learning how to administer them to students. It was really nice inside, neat, a big kitchen, dining room. They didn't pay any living costs. Their order did.

The brothers seemed happy all the time, except when they weren't. Corporal punishment for acts of disobedience was a thing in Catholic schools.

At one time or another, every classmate of mine at St. Philip Neri got "shots" as we put it.

Some brothers, like Brother Bruce, who was nicknamed "Bad Ass" by some of us, used a hefty ruler or their hands.

Brother Bruce

Brother Albert, favored a long, thin blue stick that he named "Blue Swish." You would bend over and he cracked it across your ass a bunch of times. It made a swishing sound and hurt like hell.

Brother Gwynn had an official paddle, a hefty piece of lumber (like the one pictured below). That hurt even more. I actually fought back tears once.

We all took it, though. It was sort of a weird Catholic right of passage for everyone.

And I wanted to be one of these interesting individuals. They were good teachers.

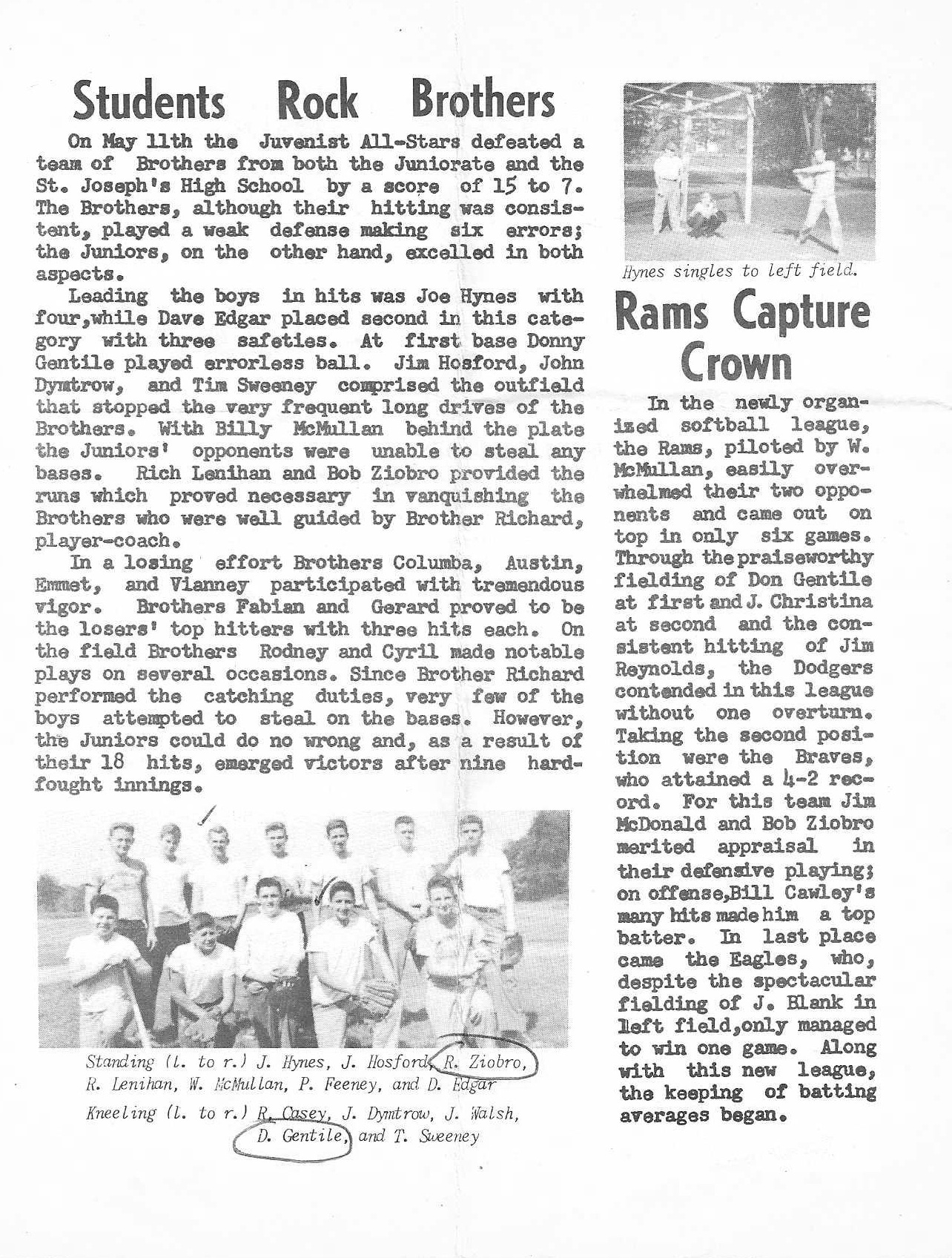

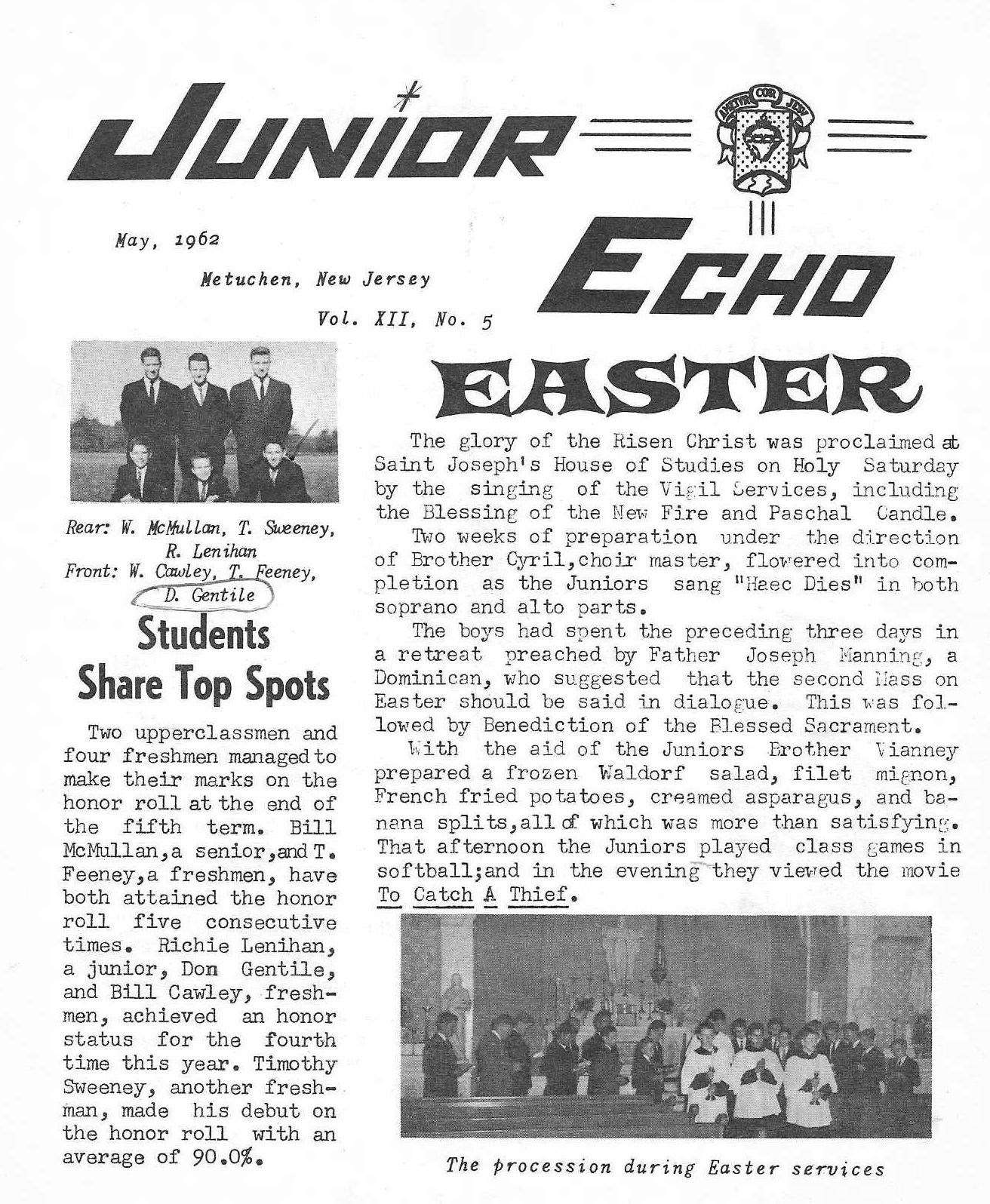

That's when I met Robert Ziobro at the St. Joseph Juniorate, where I would live and attend high school, the first step on the road to final vows.

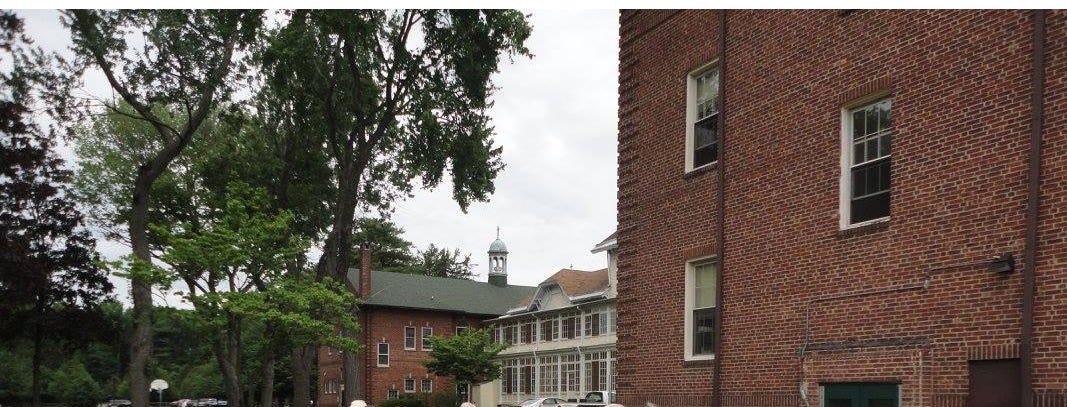

This conclave was located in Metuchen, N.J. about 47 miles from my parents' apartment in the Bronx. We just called it Metuchen.

St. Joseph’s Juniorate

I arrived with 17 other students who were all good Catholic boys from the New York City area. Counting us, St. Joseph's only had only about 30 students. The "calling" is a rare thing.

The future Brother Robert Ziobro -- we called him Bob -- was in his high school junior year when I got there. He was a strapping well-built kid from Elizabeth, N.J., the son of Polish immigrants, who spoke Polish himself.

He had the most pleasant-sounding voice. It always seemed so calm. And, even at 17, his hair was thinning.

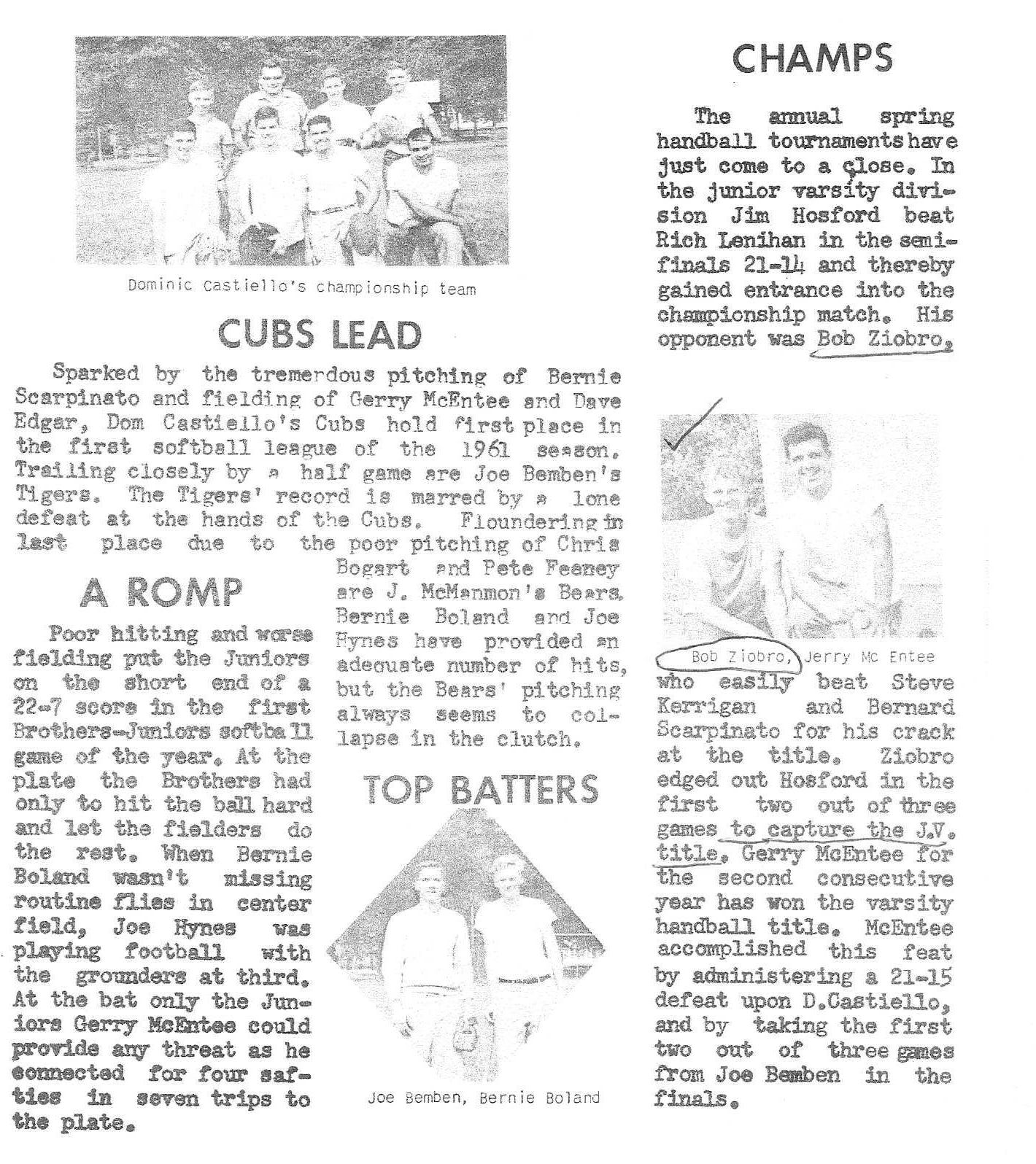

Ziobro did indeed have the "calling" and a lot of Catholic kids are better off for it. He was also pretty good at handball. The school's little newspaper, the Junior Echo, told how Bob had won the junior varsity handball tournament.

Recently, in a totally nostalgic mood, I started searching the Internet for brothers that I knew more than six decades ago.

I found obits and photos for a few. Brother Aidan, still a good-looking man in his senior years, was gone. So was "Bad Ass" Brother Bruce. And there were mentions and photos on various school websites of other brothers I had come across in my two years with them.

Then, on the Linked In website, up popped a photo of a brother wearing a goofy grin. The fellow was bald. And he was wearing that cassock I always admired.

It was Zeke. He was 77 now.

Then I found a 2012 article that reported on his accomplishments.

He'd gotten two masters degrees, one from Notre Dame, the other from Fordham University.

He taught Religion, French, English, Sociology and Psychology at a bunch of schools. He was a guidance counselor, a student council moderator, a Mother’s Club moderator (whatever that is) and a Dean of Freshmen.

He was also the Sacred Heart's vocation director for over twenty years and served as the Director of Religious Education at several Catholic parishes.

And he never lost his touch when it came to handball. At Msgr. McClancy High School, in Queens, N.Y., he was named handball Coach of the Year by the Catholic High School Athletic Association.

He had a Facebook page and many students he'd taught kept in touch. They loved him.

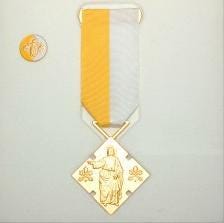

That 2012 article reported that Pope Benedict XVI had twice awarded Brother Robert Ziobro the highest honors for distinguished service that can be granted to the laity by the head of the Catholic Church.

They were the Cross Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice (For Church and Pope) and the Benemerenti Medal.

Son of a bitch! Bob!

This other article about the Polish kid I knew from high school was even more amazing. It had the headline:

"Sacred Heart Brother Attributes Healing to St. John Paul II," the Pope who was canonized in 2013.

I had to know more about this.

I made a few phone calls to places where he had toiled and found Brother Robert Ziobro now residing at the Sacred Heart's retirement facility in Pascoag, R.I.

"Donny Gentile!" he said when he returned my call. It was that same pleasant-sounding voice.

"So you remember me?" I asked.

"Of course I do."

I'll get to the miracle.

But in hours of conversation over a bunch of days, we were high school kids again, reminiscing with a lot of laughter and some talk about being Catholic (me a lapsed one) and the days at Metuchen.

My mother had saved every Junior Echo from the two years I spent at Metuchen. So I had many memories right in front of me.

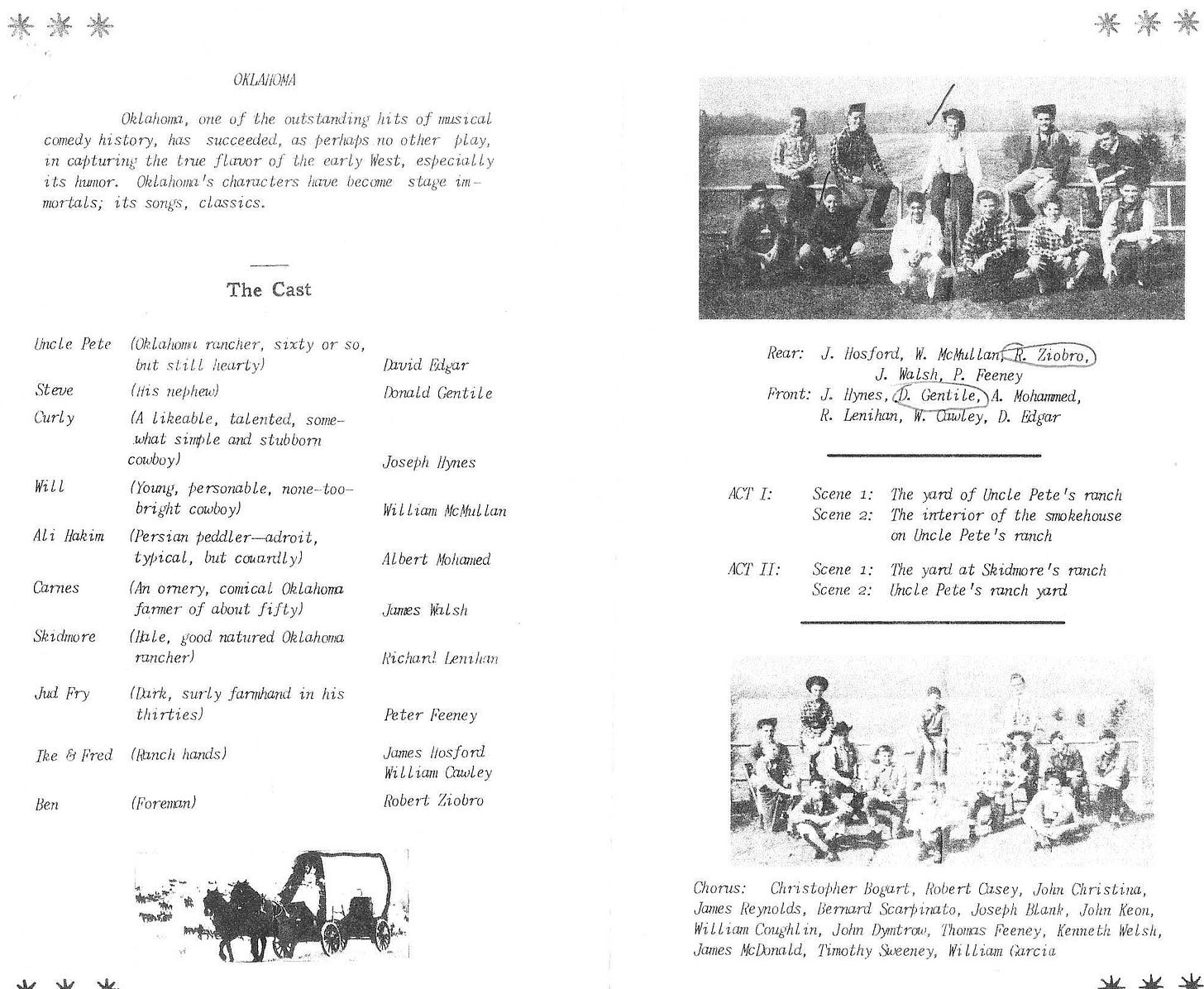

It's still a mystery to me, I told Ziobro, why in the world would we treat our parents on a visiting day to an all-male production of "Oklahoma."

A wannabe-playwright brother had rewritten most of the production and destroyed Rodgers and Hammerstein. Obviously, we didn't have female students. And performing in drag was probably not in the holy order's playbook.

Somewhat ridiculously, I thought, the ladies in the musical who couldn't be written out of the production were referred to but never seen.

I was one of the central cast members. I had two lines to sing as a character called Steve, who didn't exist in the original musical. He was the nephew of another character that didn't originally exist.

And Ado Annie, the musical's character who sings, "I Can't Say No," referring to her sexual proclivities, was gone. The song was rewritten and referred to a drinking problem.

"It was sung by another student in my year," Ziobro recalled. "Al Mohamed" -- who played peddler Ali Hakim, a real character from the play.

"I was Ben, a rancher," said Ziobro. "I had one line."

Metuchen was a huge property, with lots of woods around it. One section was an avenue of grass bordered on one side by these huge trees, a serene place, one of comfort and peace.

We prayed a lot there, especially during a three-day retreat of silence that we held each year.

There was a sports field large enough to play four softball games or two touch football games at a time. Brothers who taught us had to be on the teams to fill out the amount of players needed to create four nine-member softball squads and two touch football teams.

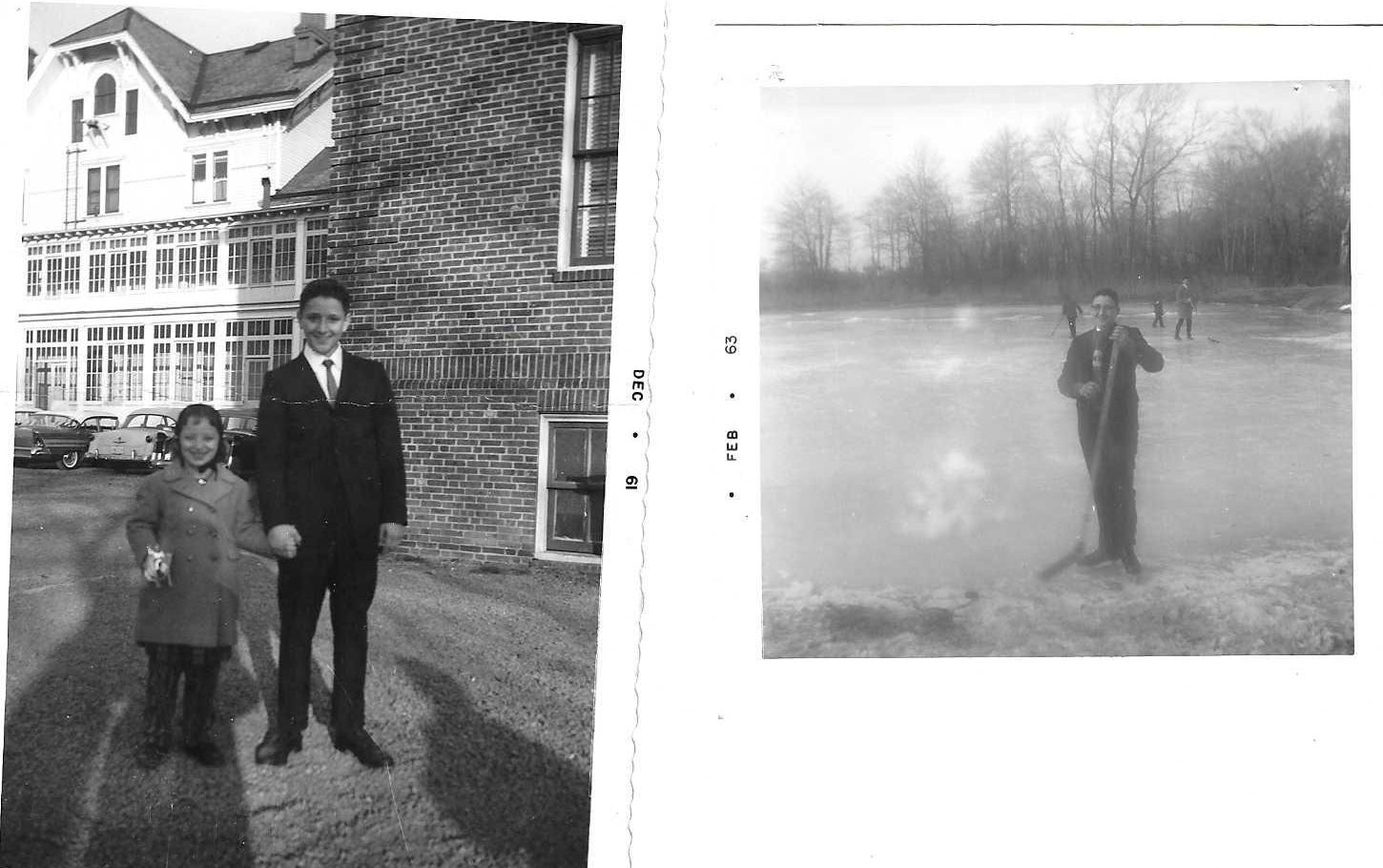

The school had basketball and handball courts and a huge pond that froze over in the winter. We played hockey there. I really sucked.

Me and kid sister during a visit. Me not falling on the ice.

We harvested a field of strawberries and froze the fruit to eat year-round as dessert toppings or homemade ice cream.

We slept in a large third-floor dormitory. Ziobro and I remembered that some students talked in their sleep.

I remember hearing one cry out, "Pass the potatoes."

At 5:30 a.m. Brother Robert, the head of our band of aspirants, clapped his hands to awaken us and shouted in Latin, "Ametur Cor Jesu" (Loved be the Heart of Jesus) to which we sleepily replied, "Ametur Cor Maria" (Loved be the Heart of Mary).

We made our beds, used the lavatory and hustled down to our study hall where we prayed in front of a large statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

Mass in the school's chapel followed. It was in a building connected by a beautiful window-glass paneled walkway to the main three-story school and lodgings. Windexing the many panels was one of the chores. I still can't use Windex the right way.

After breakfast, we went to classes. There were just two sophomores, 8 juniors, four seniors, and my freshman class of 14. We got extra attention. I made the honor roll every semester. I passed geometry even though math was always a mystery to me. I learned how to touch-type, a valuable skill for my future years as a journalist.

I'll get to the miracle.

During our talks, I told Bob that one of my most vivid memories of him had to do with his thinning hair.

Both he and I, for some reason, were picked to be student barbers. A local haircutter from the town of Metuchen came in to train us.

"I think they picked me because I'm Italian and all Italians are supposed to have the barber gene in them," I said.

"Maybe so," said Zeke.

He didn't remember but I reminded him that once, in training, I practiced on him. I just kept snipping away at his wispy locks until there wasn't much left. He had this look of horror on his face when he saw his future self in a mirror.

They didn't let me cut hair after that.

Zeke in his sophomore year class photo

On another occasion during a touch football game, Ziobro was on my team. On the opposing squad was Pete Feeney, one of the two sophomores. Feeney had it in for me. I'd given him a hard block in a previous game and he didn't like it.

He was a bruiser (he played hulking cowboy Jud Fry in our production of Oklahoma. He sang "Poor Jud is Dead." He had a good voice.) He also had a short fuse because on one play he knocked me on my ass.

I got up, brushed myself off and walked away without a word.

Ziobro, smiling and in an agitated state, came over and was incredibly congratulatory that I held my temper. He saw it as a good Catholic thing. I told him I just didn't want to make Feeney any angrier.

Aside from the physical contact we made in our sporting events, we had a rule that we never touched another student.

I learned of the stipulation early on when I put my arm around a student who'd blasted a home run in a softball game.

Bob came over. That was a no-no. "Modesty of the hands," he said.

I learned other rules the very first time I sat down for a meal at the school.

The dining hall, or refectory, as we called it, had tables with five or six students at each of them. Each table had a captain, an older student, who had the power.

You were not allowed to comment on the food. You could not say the food was good. You could not say the food stunk. You had to eat a sufficient portion of anything served.

I hated broccoli and still do. At that very first meal I had at Metuchen there sat a large serving bowl of the dreaded weed. I didn't take enough, according to my table's captain.

So he ordered me to sit in silence, which he could do, went to get more broccoli from the kitchen and told me to eat what was in the bowl, which was a substantial amount. I choked it down with slice after slice of bread.

"That same thing happened to me," Ziobro confessed.

We chatted for a while about a sort of secret rule that came into play whenever somebody left the school, which happened a lot but was never actually witnessed. My freshman class dwindled down to about 7 by the time I left after sophomore year.

"We never spoke their names after they left," I recalled.

"I know," he said. "It was also like they somehow vanished in the night and just weren't there in the morning."

Each month, I told Bob, my parents sent me a copy of Sports Illustrated. And one month, I noticed a page had a section cut out, a place where there had obviously been a photo.

Definite censorship.

On a visit home to the Bronx during a Christmas break, I got a haircut at the local barber and there among the magazines was the SI issue that had been censored.

"I had to look," I told Ziobro. "It turned out the photo that got cut out was of some college homecoming queen, nothing offensive. She wore a dress up to her neck."

If I'd stayed at Metuchen, I'd never have seen the swimsuit issue. The first one came out 1964, a year after I left.

Ziobro laughed.

One article in a Junior Echo reminded Bob and I of a bus trip we all took to NYC to visit the United Nations and attend a hockey game at Madison Square Garden.

I recalled how the bus drove slowly through traffic along 42d St., in Times Square past a string of dirty movies advertising their flicks with large marquees showing scantily clad women.

The chatter on the bus stopped and I tried to stare straight ahead as did many of our gang of good Catholic boys. Of course, I eventually looked.

I read Ziobro another article in one of our little newspapers. It reported how he'd kicked ass in a handball tournament, emerging as the junior varsity champ. He liked that memory.

Bob knew all the brothers I remembered. And he told me that it was "in the late 1960s" that the order changed its rule about picking one name and allowed members to use their given name or, if they wanted, use their chosen name and their actual surname.

"We had so many brothers whose real first name was Thomas, that a lot of them kept their chosen name," he said.

"I was Brother Douglas and didn't really like that name. My mother, however, did like it, saying, 'It was such a good name for you.'"

This from the woman who had named him Robert.

We laughed.

Of the teachers who had taught me in elementary school at St. Philip's, Ziobro knew that, in addition to Brother Aidan and Brother Bruce, Brothers Albert, the football coach, and Gwynn had passed.

"Albert, sadly, went blind before he died relatively young, in his early 60s. He was so depressed that he couldn't teach anymore," said Ziobro.

When I mentioned "Blue Swish," Brother Albert's corporal punishment device, Bob said, "He had a paddle he called 'Jose' when he taught at McClancy High School."

Bob admitted that he never wanted to hit a student, even though someone had given him a paddle when he took his final vows. "It's still in a trunk I have."

He also revealed that Brother Albert's real name was Cornelius Buckley.

"He kept Albert as his first name," said Brother Bob.

"Now I know why," I said. "Who wants to be named Cornelius?"

Brother Gwynn had died in Kenya, Ziobro said.

"How?" I asked. "A lion?"

"No, he got hit by a cab."

Bob asked me about my life and I told him I'd been a reporter and writer for the New York Daily News and the National ENQUIRER.

In 1987 at the Daily News, I told him I was assigned to cover a fatal hit and run accident that had occurred on the 59th St. Bridge in Manhattan.

A Brother of the Sacred Heart, James O'Grady, was intoxicated and driving over the bridge when he struck and killed a tow-truck operator changing a flat for a stalled motorist. The victim was a father of three.

The deputy city editor, Vince Cosgrove, knew I'd once wanted to join the Sacred Heart community so he thought I could reconnect with someone for information.

The Metuchen facility still existed, but now it was just a residence for brothers who taught at the adjacent St. Joseph's High School, a secular learning facility for boys, which had opened the year I left. The order had stopped seeking vocations among elementary school students.

I called the place and actually reached a brother I'd met.

He told me that Brother James O'Grady was an alcoholic who had kept his addiction under control and taught AA classes to fellow sufferers.

But before the tragedy, he'd lost a brother to cancer and fell off the wagon. He was in seclusion at Metuchen following his arrest for reckless manslaughter.

I told Ziobro I tried to be as kind as I could to Brother James in the article. He was later convicted and facing 15 years in prison.

"He never went to prison," said Bob. "There was a deal. He was ordered to teach at various jails, which he did for nine years."

Bob and I talked about the scandals of child molesting that wracked the Catholic Church over the years, ones that did not spare the Brothers of the Sacred Heart.

I found reports of incidents in the Canadian chapter of the order and others charges that were leveled at some brothers who taught at a school in New England.

A sadness came over Bob.

A religious group which "once had 3,000 members," now had shrunk to "about 900," he said.

I changed the subject.

"Tell me about the miracle," I asked.

Turns out, Bob had a face-to-face encounter with Pope John Paul II in 1995, when the Polish pontiff visited New York City and held a rosary prayer service in St. Patrick's Cathedral.

Brother Robert Ziobro, teaching at the time at McClancy High School in Queens, scored one of two tickets that the Sacred Heart Brothers were given to attend the event.

He was sitting at the end of a pew when John Paul passed by on his way to the altar.

"I called to him in Polish," said Bob. But Zeke hadn't used the language in a while.

"I wanted to say 'Welcome' to him but instead I said 'Merry Christmas.' He heard me and walked over. All the security people followed him."

"You should learn your Polish," the Pope told Bob.

Somewhat embarrassed, Bob said, "I will pray for you."

The Pope replied, "I will be your friend. I will pray for you."

Over the years, Ziobro survived a number of health crises, including a heart attack and colon cancer, which precipitated the removal of a foot-long section of his colon. "I've been to hell and purgatory and back," he told me.

But his medical ailments had stabilized until 2013 when a leg infection and blood clots led to the discovery of cancerous nodules in his lungs.

Doctors told him it was stage 4 cancer.

The night before a biopsy was scheduled at New York's Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, a friend drove him to St. Augustine of Canterbury Parish, in Kendall Park, N.J., where Bob had served in a religious education ministry for a number of years.

There, Father Robert Lyman, pastor, prayed over him and placed the skullcap, or zucchetto, of recently canonized St. John Paul II, on Bob's chest.

It was a comforting thing. You see, the Polish kid I knew had been praying to the Polish Pope up there in heaven.

The next day, before the procedure, and in an anesthetic haze, Bob listened as imaging equipment looked for the nodules.

Before slipping into unconsciousness, Brother Robert Ziobro heard the surgeon cry, "Where the hell are they?" as he looked for the nodules.

They were gone.

Four days later, Bob's oncologist, Dr. Michael Nissenblatt, called him to say, "You are healed."

"Can I say miracle?" Bob asked.

"I am not Catholic," Nissenblatt said. "You can use the word, 'healed.'"

More nodules reappeared in November 2013, but again, a relic of St. John Paul II was touched to his chest. The nodules were removed and he was given a clean bill of health.

"The doctors told me 'You should have been dead three times,'" said Bob, who remembered thinking, "My work is not yet finished."

Word of his healing spread and Brother Robert Ziobro was sent relics of the sainted Pope -- three sets of rosaries that had been touched to the Pope's crypt at the Vatican, and another purporting to be a piece of the cassock the Pope wore when he'd been shot and wounded.

"I would lend the rosaries out to people and after a while, they were never returned and I'd forgotten who I gave them to," Bob said, with a laugh.

The Vatican, apprised of Bob's healing, initiated an investigation, to see if it could be declared an official miracle attributed to the sainted Pope.

"I was supposed to go to Rome to bear witness, along with three other people who said they were healed by John Paul," but a family crisis kept him from going, Bob told me.

So how does he know it was a miracle, I asked.

"Because he did it," Bob replied.

Who was I to argue?

My last conversation with Zeke occurred at the end of May but I was looking forward to more. The last thing I said to him was "Ametur Cor Jesu." He replied "Ametur Cor Maria."

In early June, I was searching online for more photos of Bob to use with this story.

Clicking on one I hadn't found before, I was directed to the Brothers of the Sacred Heart Facebook page.

Under the photo was this:

"BROTHER ROBERT ZIOBRO, S.C., 77, a resident of Pascoag, RI, since the spring of 2019, died. . .on June 7, 2023, at 3:30 AM."

No more miracles. He'd gotten to the end of that stairway to heaven.

The notice went on, "This larger-than-life, jovial personality successfully reached even the most distant young person, and his willingness to celebrate their smallest of accomplishments – especially with pizza, pasta or cheesecake, made him a favorite 'Brother' among the young and the young at heart."

That was an accurate description.

On June 17, Brother Robert Ziobro was buried at the Brothers’ cemetery on the grounds where the complex that used to house the juniorate in Metuchen, N.J., still stands, the place where I first met Zeke. I'll be praying to him from now on.

Ametur cor Jesu. . .

Don, I worked with you for at least a decade and never saw this side of you. Thank you for sharing it with us. Zeke sounds like one of the good people. As an aside, I came within 1 point of winning a math scholarship to the St. Joseph’s that replaced your school. Luckily, my family couldn’t afford the tuition, so I was able to go to a coed high school.

Great article, Donny.

May your friend rest in peace!